Every year, Cinemalaya reminds us why the dark of a theater still feels like a sacred place.

But this year, something shifted. The 21st Cinemalaya Independent Film Festival didn’t just show films, it opened scars. The stories were louder, braver, and painfully human. They were proof that Philippine independent cinema isn’t gasping for relevance; it’s roaring for truth.

For anyone who grew up chasing screenings, scribbling notes in the dark, or arguing over frame ratios with friends after midnight, this year felt personal. Cinemalaya 21 wasn’t about escape. It was about endurance.

CINEMARTYRS AND THE PRICE OF CREATION

Sari Dalena’s Cinemartyrs was the kind of film that silences a room without needing to ask.

Winner of Best Director and Special Jury Award (Full-Length), Dalena’s work is a requiem and a revolt. It’s cinema that breathes and bleeds at the same time, an act of remembering the artists who gave everything for their craft and the country that often forgets them.

Teresa Barrozo’s Best Original Music Score turned pain into sound, echoing like a sermon inside an abandoned chapel. There are moments where the film doesn’t seem to play at you, but through you, raw, spiritual, fevered.

Dalena doesn’t romanticize suffering; she testifies to it. And that honesty is rare. You leave the theater with your pulse slower, your chest heavier, your love for film strangely deeper.

Cinemartyrs is the soul of Cinemalaya 21, a film about making films when the world stops caring if you do.

BLOOM WHERE YOU ARE PLANTED: QUIET AS REVOLUTION

Noni Abao’s Bloom Where You Are Planted, the festival’s Best Film, is a study in stillness.

There’s no spectacle here, no grand speeches, no melodramatic rescues. Just ordinary lives caught in extraordinary persistence. Edited with quiet brilliance by Best Editing winner Che Tagyamon, every cut feels deliberate, like a held breath before a confession.

Abao’s vision of resilience is intimate and unsentimental. It’s the kind of storytelling that feels like memory, not narrative. In a festival full of movement, Bloom was the pause that demanded reflection.

PADAMLÁGAN: ARCHITECTURE OF GRIEF

Jeric Delos Angeles’ Best Production Design win for Padamlágan might be the most poetic citation of the year.

The film, inspired by the Colgante Bridge tragedy, doesn’t just recreate space, it resurrects it. Every wall, bridge, and surface holds the texture of loss. You can almost smell the metal, feel the moisture in the wood, hear the echo of footsteps that never made it across.

Delos Angeles doesn’t decorate scenes; he builds memory. His design work turns Padamlágan into a living artifact, one where history doesn’t just exist, it haunts. This film deserves to be studied frame by frame, not for its polish but for its honesty.

WHEN HISTORY BIT BACK

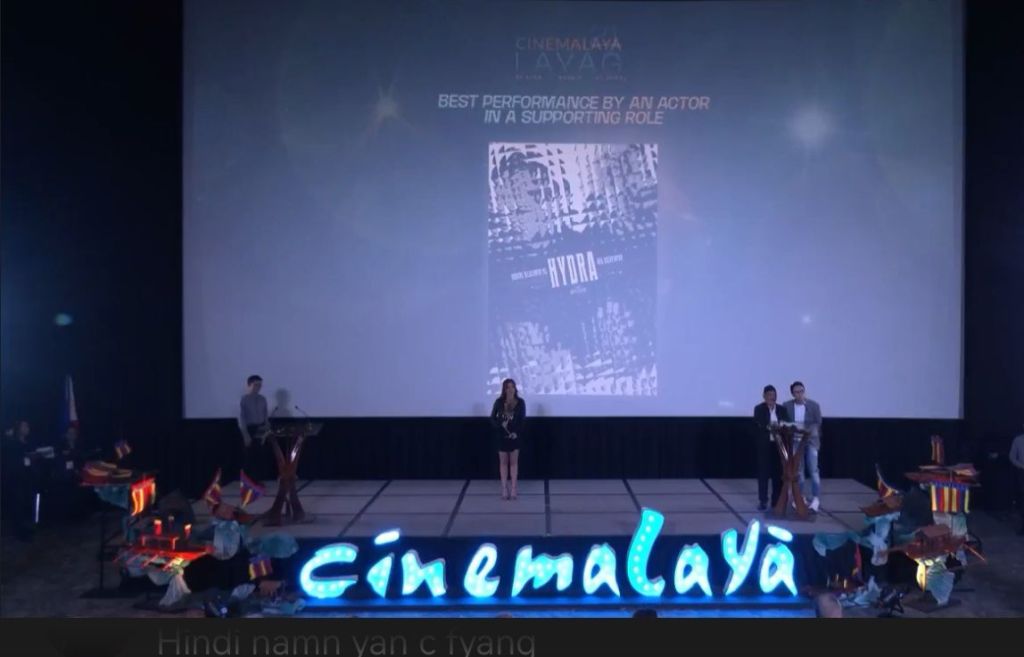

Habang Nilalamon ng Hydra ang Kasaysayan devoured the acting categories, Best Actor (Jojit Lorenzo), Best Actress (Mylene Dizon), and Best Supporting Actor (Nanding Josef).

The trio delivered performances that felt both ancient and new, grounded in historical fatigue but lit by moral urgency. The film isn’t content to retell history; it interrogates it. Hydra’s multiple heads aren’t monsters, they’re metaphors for the way truth keeps splitting when no one’s brave enough to name it.

THE FILMS THAT REFUSED TO BE QUIET

Child No. 82 (Son of Boy Kana) by Tim Rone Villanueva, co-written with Herlyn Alegre, earned Best Screenplay (Full-Length), Best Supporting Actress (Rochelle Pangilinan-Solinap), and Audience Choice (Full-Length), deservedly.

Villanueva writes with restraint and directs with clarity. His world is harsh but not hopeless. It’s a film that understands pain not as spectacle, but as inheritance.

Meanwhile, Raging claimed Best Cinematography (Theo Lozada) and Best Sound Design (Lamberto Casas Jr.), a sensory rush of fury and movement.

Open Endings gave us the collective strength of Best Ensemble Performance winners Janella Salvador, Klea Pineda, Leanne Mamonong, and Jasmine Curtis-Smith, a rare chorus of women in sync.

And Renei Dimla’s Republika ng Pipolipinas, NETPAC Award (Full-Length) winner, reminded us that satire can wound just as deeply as grief.

THE SHORTS THAT STRUCK LIKE MATCHES

If the full-lengths were slow burns, the shorts were sparks. The Next 24 Hours by Carl Joseph Papa (Best Film, Short) animated grief with devastating tenderness.

I’m Best Left Inside My Head by Elian Idioma (Best Director, Short) turned anxiety into architecture.

Maria Estela Paiso’s Kay Basta Angkarabo Yay Bagay Ibat Ha Langit (Objects Do Not Randomly Fall From the Sky) (Special Jury Award, Short) blurred dream and memory with stunning control.

Handiong Kapuno’s Figat (Best Screenplay, Short) and Daniel de la Cruz’s Hasang (Gills) (NETPAC Award, Short) carried the pulse of water, restless, vital, and alive.

And Ascension from the Office Cubicle by Hannah Silvestre (Audience Choice, Short) might be the most quietly subversive, a satire that’s both confession and cry for help.

A NATION OF STORYTELLERS

Cinemalaya 21 proved that Filipino cinema isn’t a genre. It’s a geography… vast, unpredictable, and sacred.

These films remind us that our stories don’t end in trauma; they transform through it. From Cinemartyrs’ sacred fury to Padamlágan’s silent grief, Bloom’s resilience, and Hydra’s reckoning, this was the year our wounds found form and called it film.

And somewhere in that darkness between reels, we were reminded: We don’t watch films to escape.

We watch to remember.

Leave a comment